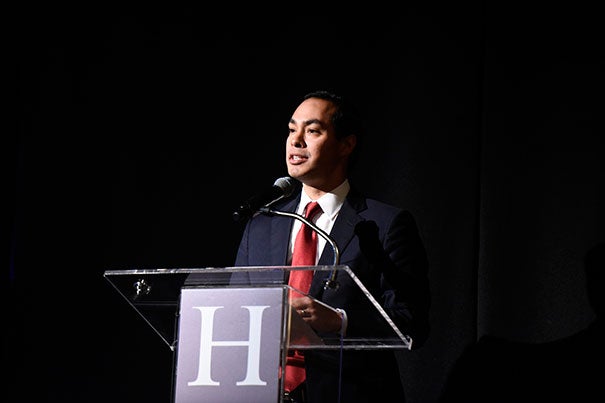

Harvard Alumni Association President Paul Choi ’86, J.D. ’89, welcomes alumni to the latest Your Harvard event in Atlanta.

Photos courtesy of HAA

The fight for equality in education

Your Harvard session in Atlanta probes ways in which system has fallen short, could improve

ATLANTA — Quoting civil rights lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston, LL.B. ’22, S.J.D. ’23, Jonathan Walton, Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church, opened the latest Your Harvard event in Atlanta by saying, “Once again it bears repeating that this fight for equality of educational opportunity is not an isolated struggle. All of our struggles must tie in together, and they must support one another. … Maybe the next generation will be able to take time out to rest, but we have too far to go, and we have too much work to do. So you can shout in victory if you want, but don’t shout too soon.”

Speaking of Houston’s decades-long fight to dismantle the Jim Crow laws affirmed by Plessy v. Ferguson, Walton noted that “as the dean of Howard University School of Law, Houston did more than just train lawyers,” adding, “He trained social engineers.”

A few years after Hamilton’s death in 1950, one of those protégés, Thurgood Marshall, argued the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court, the case that overturned the practice of “separate but equal” public school systems. However, despite the great strides of these social engineers, inequality in public education continues.

Speaking to more than 350 local alumni and friends gathered at Atlanta’s Woodruff Arts Center earlier this month, two Harvard faculty members whose work examines inequality in education addressed the issue.

To date, the Your Harvard series — an effort of The Harvard Campaign to allow alumni to connect with each other and engage with some of the most exciting scholarship underway on campus — has attracted more than 3,500 alumni in nine cities.

Roland Fryer Jr., the Henry Lee Professor of Economics and faculty director of the Education Innovation Laboratory, was not only the youngest African-American to receive tenure at Harvard, but also the only African-American to be awarded the John Bates Clark Medal, given to the best American economist under age 40. He was joined in the conversation on “education as a universal civil right” by Professor Meira Levinson, an award-winning scholar at the Harvard Graduate School of Education whose work explores the idea of civic education. Mary Louise Kelly ’93, an Atlanta native and former reporter for NPR, CNN, and the BBC, served as moderator.

Levinson acknowledged a fundamental lesson that gives her hope that the problem can be addressed. Having taught middle school students in both Atlanta and Boston school districts, she said, “I never met an eighth-grader who wasn’t eager to learn.” She also noted that we tend to take an aggregated view of the American education system. “If you disaggregate,” Levinson noted, “we are doing extremely well … in much of the U.S. system, and poorly in some of the rest of the U.S. system.”

The event featured a talk with Mary Louise Kelly ’93 (from left) and Harvard Professors Roland Fryer and Meira Levinson, and Julian Castro, J.D. ’00, secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

So the challenge becomes learning from and replicating the things that work for the benefit of school districts throughout the country. The method for doing so remains a work in progress. Fryer likens conversations with successful charter school leaders to hearing his grandmother relay a recipe by using “a palm” as a unit of measure — each school has its own, unique, way of doing things. But, if you can get to the root of those efforts, Fryer found they can be transferable.

He says he was able to boil successful schools down “to five things that explain 50 percent of the variance”: increased instructional time, more-effective teachers and administrators, high-dosage tutoring, data-driven instruction, and a culture of high expectations. Injecting those practices into 20 of the lowest-performing public schools in Houston showed a significant, positive impact.

Well-trained instructors are also a key piece of the puzzle, Levinson said.

“Almost no human being wants to lead a life where they feel like a failure,” she said. “As teachers, if we can reach out and recognize that those young people actually do have hopes … and say, … ‘We’re going to help show you how to channel those aspirations,’ I think that that can always make a difference.”

It’s a daunting task, Fryer agreed, but he contended that instruction is secondary to basic educational opportunity. “The school day is seven hours” for students, he said. “You’ve got seven hours to make up for poverty. You’ve got seven hours to make up for the fact that 90 percent of them are in female-headed households. Seven hours.”

The gaps in African-American advancement since 1964, he noted, improved dramatically when looked at through the lens of eighth-grade performance. “Education is … the civil rights issue of the 21st century. And it couldn’t be more important at every level and in every part of our democracy,” he concluded.

The two professors agreed that Harvard has a significant role to play in education, both for its students and for the global good — a point echoed by Harvard President Drew Faust.

Again invoking Houston, Faust quoted, “All our struggles must tie in together and support one another. … We must remain on the alert and push the struggle farther with all our might.”

“Tying in together and supporting one another — it is a powerful concept, and in many ways describes what the Harvard community has done for nearly four centuries,” Faust said. “It’s up to us to ensure that we continue to build, to lead, to serve, and to advance in a world that is almost unimaginably different from the one our founders inhabited nearly four centuries ago, or even from the one Charles Hamilton Houston described in 1936.”