During the Revolutionary War, Harvard turned its campus over to the military, and set up shop 20 miles away, in Concord, Mass.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard’s year of exile

During the American Revolution, the College moved to Concord

As Harvard celebrates its 375th anniversary, the Gazette is examining key moments and developments over the University’s broad and compelling history.

Lexington and Concord. April 19, 1775. Where and when the Revolutionary War started is well known.

Not so well known is the fact that Harvard played an important, if odd, role afterward in the early days of the Revolution, turning its campus over to the nascent American army. On May 1, 1775, undergraduates were dismissed and given an early summer vacation. Classes resumed on Oct. 5 in Concord, 20 miles away — the beginning of a wartime academic sojourn.

Student safety was a factor in the move, said historian John L. Bell, a specialist in the early days of the war, but so was a worry that students would consort with rough and tumble soldiers. “There was discipline,” he said of the American army gathering in Cambridge. “But it wasn’t college discipline.”

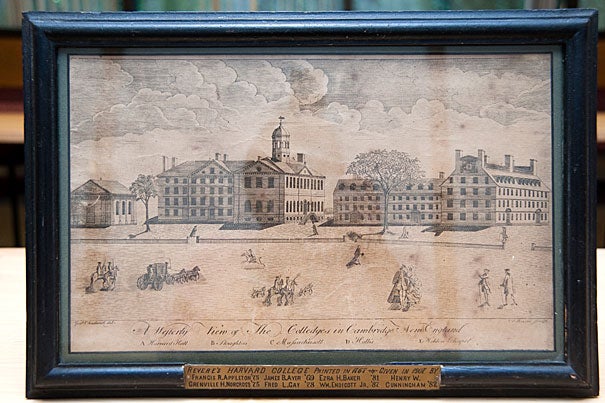

Harvard’s move to Concord also served a practical military purpose. Provincial troops fortifying Cambridge during the siege of Boston needed places to stay. The five Harvard buildings were used to house 1,600 soldiers — more than the population of Cambridge at the time. Hollis and Massachusetts halls each held 640 soldiers; Stoughton Hall (razed in 1781) was home to 240; and tiny Holden Chapel bunked 160. Harvard Hall — the College buttery, library, and social space — served a similar function. Tents and rude barracks sprang up in Harvard Yard, and soldiers built a defensive breastwork on high ground near Quincy Street, where Lamont Library now stands.

Harvard was not on the front lines, said Bell, since most of the nearest fortifications were built in East Cambridge and parts of what is now Somerville. The new war did not bring “physical disruption” to Harvard, he said, so much as “social disruption.”

Social disruption also accompanied Harvard’s move to Concord. The library was shipped there, along with the College fire engine, the museum, and even the Ellicott Regulator Clock, a key item of “philosophical apparatus” valued for its precise astronomical timekeeping.

Harvard students took rooms in Concord where they could, including a dozen who boarded with Dr. Joseph Lee, who was under house arrest as a British spy. Classes — reduced to two recitations a day in winter — were held in a deserted grammar school, and in Concord’s courthouse and the First Parish meetinghouse.

Jenny Rankin, M.Div. ’88, one of First Parish’s current ministers (and the first woman to hold the title), is intrigued by “the thought of this small, sleepy town being invaded by boys.” Harvard’s Concord interlude has been much on her mind, since First Parish celebrates its own 375th anniversary this year. The Concord church opened in 1636, the same year as Harvard College.

The meetinghouse where Harvard’s exiled students gathered burned down in 1900, said Rankin, but a few artifacts remain: an oaken beam, some iron keys, communion silver, and two pews — whose hardness was a source of undergraduate complaints.

What was Harvard’s stay in Concord like? Interpretations vary. Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison called the interlude “a not unpleasant Babylonian Captivity at the future shrine of New England letters.” Historian and poet Charles A. Wagner wrote that “one hundred students were spread through little Concord’s taverns, homes, meetinghouse and courthouse, to the unexpected joy of the Concord maidens.”

But some documents intimate that Concord was no picnic. Students were bored by country life, supplies were scant, smallpox hovered, and the winter of 1775-1776 was harsh. Rented rooms were chilly and distant from makeshift classrooms. The fall and spring vacations were canceled. By April, 1776, a Harvard resolution noted “the prevailing Discontent” among undergraduates “on account of their being detained at Concord.”

Part of the unhappiness was that Concord was crowded. By March, 1776, the town’s population had swelled to 1,900 — 25 percent higher than the year before. The Provincial Congress had ordered towns in Massachusetts to take in Boston’s poor fleeing the British occupation. Concord’s quota for the poor was 66, but it found room for 82. The Harvard undergraduates in many ways were simply among the displaced persons.

The British surrendered Boston in March, 1776, but the American troops who had bivouacked around Harvard Yard inevitably left a trail of damages when they moved south. The soldiers whom Harvard President Samuel Langdon called a “glorious army of freemen,” tore off the roof of Harvard Hall — 1,000 pounds of metal – to melt into bullets. They stripped brass doorknobs and box locks out of the buildings, along with interior woodwork. In 1778, Harvard petitioned the Massachusetts House of Representatives, listing losses down to the shilling and pence. The College was awarded the sum of 417 pounds.

Permission for the College to reoccupy Harvard Yard came on June 11, 1776. The next day, Langdon wrote a formal letter of thanks to Concord town officials. It included the hope that there had been no “incivilities or indecencies of behavior.” That same month, the College elected to pay Concord, for its trouble, the sum of 10 pounds.

To learn more about Harvard’s celebration and history, visit the 375th anniversary website.