Archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff discusses the memorabilia that tells the story of The Harvard Lampoon throughout its 140 years.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Smirk central

Lampoon’s creative irreverence animates exhibit marking its 140th anniversary

For generations, Harvard and humor have gone hand in hand. From “The Great Butter Rebellion” of 1766, when students proclaimed the butter “stinketh,” to a notice posted in 1903 by undergrads urging their classmates to return home due to a (phony) diphtheria outbreak, to the annual hilarity of the Hasty Pudding Theatrical’s musical, it seems mischief and mirth have always been part of campus life.

Now one bastion of Crimson irreverence is lifting the curtain on its history, influence, and inner workings.

The Harvard Lampoon first appeared in February 1876. Inspired by the London-based Punch, the Harvard humor magazine blended written satire with witty illustrations. The mission of its seven undergrad founders was simple, if open-ended: “Have a cut at everything around us that needs correction.”

For almost a century and a half that founding ethos has endured. In honor of the magazine’s 140th anniversary, Harvard University Archives is hosting an exhibition of memorabilia that tells the story of The Lampoon through the years. Though archivists have collected Lampoon material for decades, more recently — spurred in part by the 2009 centennial of the its famous building — they began a more formal conversation with magazine trustees about how best to preserve the publication’s eclectic ephemera.

The exhibit ‘shows people what we have been up to creatively for over a century.’ — Mark Steinbach ’17

“Essentially, students take things home,” said archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, who helped curate the show. “They might find them years later and send them back to us. We have started to amass a considerable amount of material.”

Alumni and students, she added, “are interested in working with us and bringing in more.”

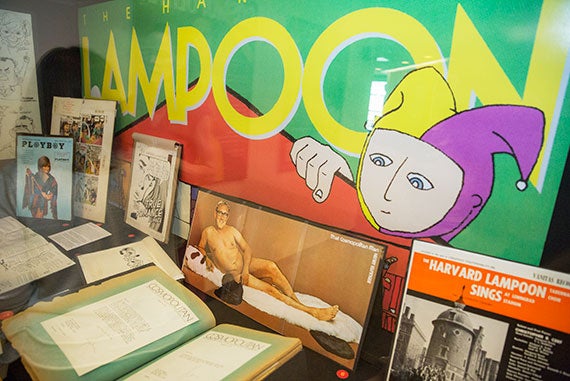

“Remorseless Irony and Sarcastic Pens: The Story of the Harvard Lampoon,” on view through Oct. 2, features a sampling of Lampoon-related treasures in five display cases and along several walls of Pusey Library’s ground floor. Original and digitally reproduced manuscripts, sketches, scrapbooks, clippings, magazines, posters, and parodies all help paint a picture of the magazine and how it has shaped and been shaped by campus life and the world beyond Cambridge.

“It’s a good chance to see how The Lampoon has fit into Harvard as a whole,” said current Lampoon president Mark Steinbach ’17. The exhibit, he added, “shows people what we have been up to creatively for over a century.”

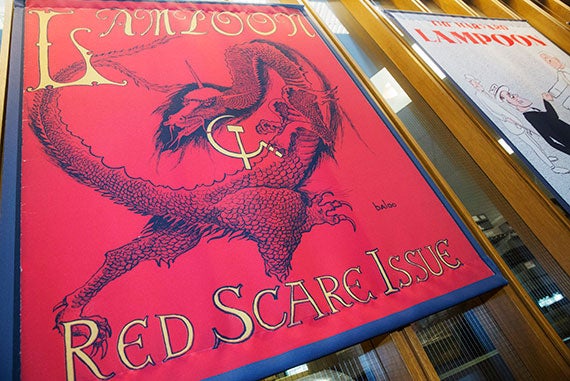

Along one wall several covers highlight the influence of politics on The Lampoon. An illustration of Teddy Roosevelt appeared in 1905. Later cover drawings depicted Franklin Roosevelt shaking the hand of the John Harvard Statue, and presidential candidates Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy riding dodos and waving small American flags. The cover of the “Red Scare Issue” in 1950 featured a red dragon with a hammer and sickle stuck in its claws.

You can see the writers “were absolutely being affected one way or the other by the outside world, and their thinking about what they were walking into, what they were reacting to,” said Sniffin-Marinoff.

Other covers point to The Lampoon’s love of parody, including one of the magazine’s most famous spoofs, a take-off of a 1972 Cosmopolitan issue complete with the image of a buxom, cross-eyed brunette next to the headline “How to Tell if Your Man is Dead,” as well as a centerfold of Henry Kissinger, his head superimposed on a naked cabdriver. Nearby, a letter from Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown, who had seen advance proofs of The Lampoon issue, encouraged the students to tone down their sexy headlines and swap out the woman on the cover with an image of one who appeared more upbeat.

More like this

“She looks gloomy,” wrote Brown, “which is always a put-off.” Readers weren’t put off. The issue broke sales records.

No exhibit on The Lampoon would be complete without a nod to its famous pranks. Last summer Lampooners fled for New York with The Crimson president’s chair, and there posed as Crimson staffers and convinced Donald Trump they backed his presidential bid. Proof of the escapade, a photo of Trump sitting in the celebrated seat, is included in the show.

To highlight the range of talent that has passed through The Lampoon’s doors, the first exhibit case features a rotating item from the collection. Currently it holds “Bayeux Travesty,” a cover from 1966 by the late David C.K. McClelland ’69 that many consider the magazine’s finest. A faithful take-off of the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England in 1066, McClelland’s drawing tells the story of a football victory over Yale.

Other gems include cover art by Fred Gwynne ’51, who went on to play Herman Munster in “The Munsters,” along with a book of drawings and poems by John Updike ’54. Additional artwork and text from writers and illustrators who found fame at The New Yorker, Life, and in shows such as “Seinfeld” and “The Simpsons” point to The Lampoon’s status as a talent farm.

“A lot of Lampoon grads were on the ground floor of “The Simpsons,” said Ted Widmer ’84, who crossed paths at the magazine with future “Simpsons” writer and late-night star Conan O’Brien ’85.

Widmer ultimately turned his professional focus to politics and history, but the author said he often injects humor into his work and regularly relies on other lessons from his Lampoon days when putting his thoughts on the page.

“Not trusting everything that you are told, looking for human interest in everything, especially in the official narratives that governments and institutions tell, and just always trying to look at everything in a fresh new way,” said Widmer, “I got all of that from the Lampoon.”

Before landing writing gigs with HBO’s “Veep” and then Fox’s “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” the first African-American woman to run The Lampoon, Alexis Wilkinson ’15, told the Gazette her work with the magazine was a critical piece of her Harvard education.

“Anytime I have free time, I’m going to be at The Lampoon if I can,” she said. “I’m going to be thinking about The Lampoon, talking about The Lampoon, I’m going to be working on it. In a lot of ways to me, it’s more important than classes.”

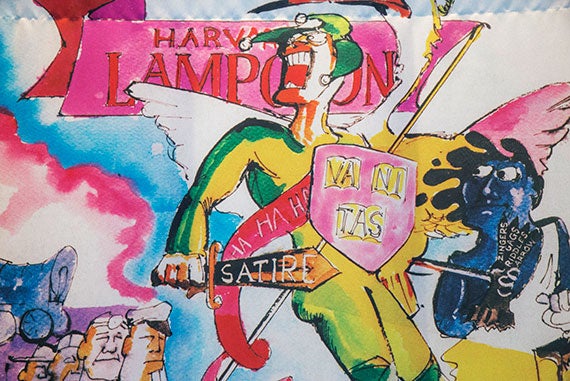

Along an entire wall hangs the largest artwork in the show, a montage created by Michael Frith ’63, another former Lampoon president. Now a member of the magazine’s graduate board, Frith worked as an editor for Theodor Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss, at Random House, and later became executive vice president and creative director for Jim Henson Productions, where he helped design beloved Muppets such as the Swedish Chef, Dr. Teeth, and Fozzie Bear.

Seven years ago, in honor of the 100th anniversary of the Lampoon Castle, Frith created the drawing for the magazine’s holiday card. His piece, “Ghosts of Christmases Past,” features a festive celebration among the magazine’s notable dead.

“I was thinking if some of those people could have gotten together for that centennial party, who would those people have been, what would it look like, and how interesting might it have been to attach some faces to those famous names.”

In Frith’s bash, Lampoon founder Ralph W. Curtis, Class of 1876, mingles with “Animal House” co-writer Douglas C. Kenney ’68, author George A. Plimpton ’48, Updike, and numerous other Lampoon luminaries.

Like many, Frith hopes the Harvard show will lead to a greater appreciation of The Lampoon’s contribution to “American culture all across the board.”

The magazine, he added, holds “a long and fascinating history with some of the most extraordinary people who have gone out into the world and really made a mark for themselves and changed the way America works from a very artistic and creative” point of view.

For Steinbach, the show highlights something else: The Lampoon’s role in helping Harvard students, and the wider world, not take themselves too seriously.

“Harvard can kind of be a serious, self-important place, and The Lampoon likes to be a reaction to that.” That reaction, he added, is key “because you can’t take things too seriously, and The Lampoon embodies that.”